From our first collaboration on ‘Firefly’ (2023), where we aimed for a children’s storybook aesthetic, Zig Dulay and I developed a working system that carried over into our next project ‘Green Bones’. By the time we began discussing its visual direction, we were already speaking the same creative language. Zig is a very collaborative filmmaker with a clear vision — which is essential in a director-cinematographer partnership. A film’s cinematography begins not with lenses or lights, but with shared values and aligned aesthetics.

The key to a meaningful work lies in syncing your perspective with the director’s. Based on experience, it’s going to be a struggle making that film if your visions diverge. Fortunately, ‘Green Bones’ also had the advantage of a long-time collaborator- production designer Mao Fadul; whom I have worked with in many of the films I’ve shot — ‘Bwaya’ (2014), ‘Oda Sa Wala’ (2018), ‘Blue Room’ (2022), ‘About Us But Not About Us’ (2022). With Zig and Mao, we shared a common language rooted in authenticity.

A New Direction

In our early conversations, Zig and I agreed that ‘Green Bones’ should look and feel differently from ‘Firefly’. While ‘Firefly’ leaned toward classical compositions— a sense of order and visual harmony; ‘Green Bones’ called for something raw, spontaneous, and more grounded because of the story. We went for a naturalistic and minimalist style, leaning into neorealism but steering clear of the gritty, overly-textured look common in similar genres.

The camera became another character that needed to reflect, and captured the emotional and physical movement of the characters. There was restraint in doing grand, sweeping shots. Instead, we opted for subtle camera movements that felt like a whisper in a crowded room- understated, but intentional. Often, we’d redo takes simply because the camera’s timing disrupted the rhythm we were after.

We primarily used two Sony Burano cameras with Sigma Cine lenses, mounted on various rigs about 80% of the time:

- A dolly platform with 32-foot tracks

- An 8-foot Porta-Jib for small vertical motion

- A gimbal for long follow-shots

- A 25-foot crane for the one shot wide-to-closeups

- DJI Inspire drone with a 50mm lens for lingering aerials

As a cinematographer, my job isn’t just to operate and direct the camera—it’s to orchestrate the visual experience intended for the big screen; always thinking about how each shot fits into the final cut. With so much content being produced these days for a 50-inch TV screen, we sometimes forget to give the audience a cinematic theatrical experience. Even though Zig and I never explicitly discussed the film’s editing rhythm, we intuitively followed a shared tempo during the shoot.

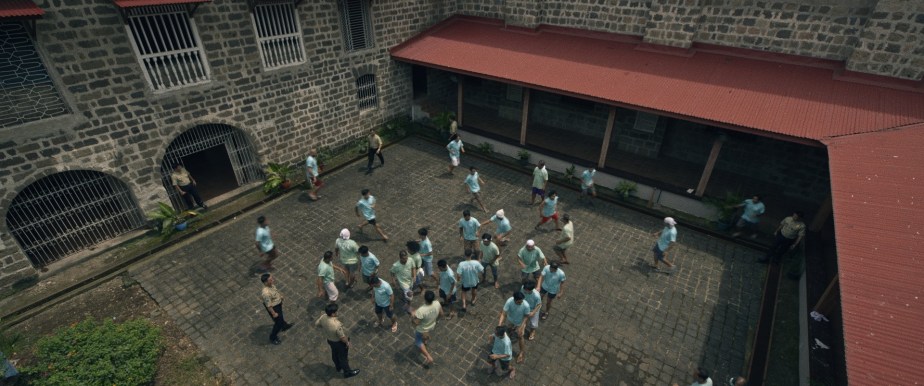

The Challenges of San Fabian

The fictional San Fabian Penal Colony—patterned after the Iwahig Prison and Penal Farm—was one of the most logistically-challenging parts of the production. In an ideal world, we would have built the entire prison on a backlot; but with budget and time constraints, we had to find creative ways to make things work. Zig’s vision and Mao’s design served as a visual blueprint, allowing us to stitch together multiple locations into one cohesive space.

The warden’s office was filmed inside the Magdalena Church in Laguna. The prison entrance and approach roads were in Pangasinan. The pier was in Bataan. The cell blocks were in Subic. And the “Tree of Hope” was located in Calatagan, Batangas. A single scene might begin shooting in Laguna and end in Batangas. This created a huge challenge for lighting continuity. Matching the quality and direction of light, as well as color temperature and actors’ screen direction, became paramount. In this case, lighting a scene is the easy part; the real challenge is sustaining consistent lighting and visual continuity across the entire film.

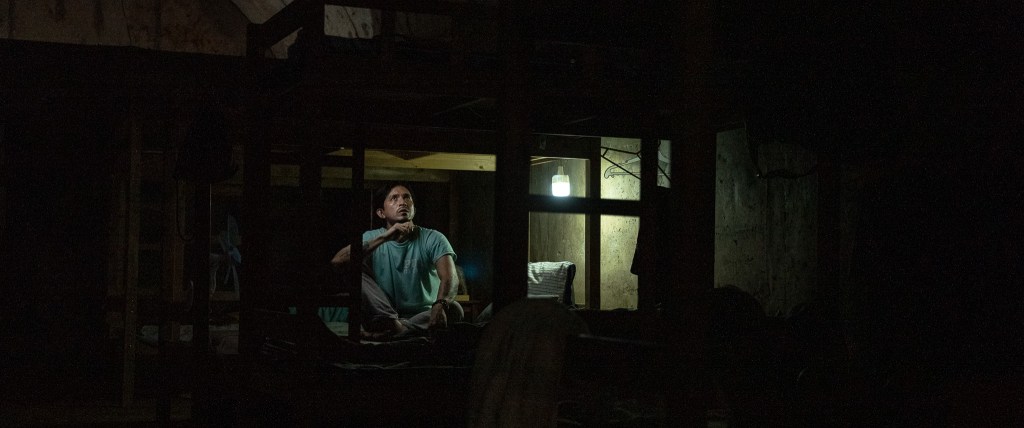

Day-for-Night Scenes

Day-for-night is a cinematography technique where scenes meant to be night scenes are actually filmed during day. It is usually done because of logistical reasons. It’s a technique that either works seamlessly or fails conspicuously, and there’s rarely a middle ground.

In ‘Green Bones’, a particular sequence on a beach location required a day-for-night treatment across multiple scenes. The isolation cell scene toward the end where Dennis Trillo escapes, was shot as night in an abandoned hospital in Bataan. The next scene, where Dennis is about to escape with his niece was shot as day-for-night at a beach in Batangas, and then cuts to Dennis running to the burning cell block shot as night in Subic, This wasn’t a stand-alone flashback or dream sequence; it was a continuous moment in the story building up to the climax, so believability was crucial.

If I’m confronted by the need to shoot day-for-night scenes, I usually need to ask myself these few key questions:

- Can I realistically light this scene as a true night shoot, especially on a beach, given our time and budget?

- How long is the scene, and how long can we hold the audience’s suspension of disbelief?

- What’s the sun’s angle during the shoot? Will it pass as moonlight when color graded?

- Most importantly, is the audience already emotionally-invested enough to accept the illusion by the time the day-for-night scene comes out?

It’s in this kind of situation that I see the very thin line between the craft and the business side of filmmaking. It creates a balancing-act moment internally, and the need to remind myself of the vision of the film. It’s a struggle between serving the story and helping out on the production cost without selling out your craft.

Shooting this sequence as a night-for-night would have required three nights, two grip trucks, and two generators—resources we didn’t have. So we lit it during the day and pumped in 6K and 4K lights for the frontal faces of the actors to control contrast, and relied heavily on color grading in post production. Knowing that Marilen Magsaysay is my colorist even before I shot the scene made me a little more confident. A long-time collaborator in a lot of my films, Marilen helped us craft a convincing night look.

The next question is—did it work? That’s for the audience to decide. Taking risks will always be part of making films, which makes it an exciting art form; and hopefully, you learn something new along the way.

Subtlety as a Statement

The cinematography of ‘Green Bones’ is grounded in three words: simple, minimal, and real. I designed each scene with restraint, always in service of the story. My visual taste leaned towards the minimal, and that sensibility guided my choices on the set.

The creative process of this film felt instinctive, thanks to the trust and talent of the people I worked with. ‘Green Bones’ is a film about choosing to be a good human being- above all else. That message resonated with me, especially in an industry where the daily grind and commercial pressures can sometimes drown out our better selves. In the end, all the team’s efforts were worth it because the story of ‘Green Bones’ mattered- and we tried to tell it with subtlety, grace, and conviction.

Behind the scenes